Mesh networking for small networks appeared in 2015 with the claim that it would solve Wi-Fi problems by improving coverage, speeding networks, and eliminating hassle. It also promised to remove the need to place base stations meticulously around a home or small office to avoid dead and slow spots.

Five years after its initial widespread emergence, those promises appear to have been fulfilled. Mesh networks have become the best way to set up a new network that spans more than a single, standalone Wi-Fi gateway can manage—or to overhaul an existing inadequate or outdated one.

Cost remains an object: Because you need at least two “nodes,” or network devices, to make a mesh, and three is more typical, you can spend two to five times as much compared to old-school Wi-Fi base stations that can’t connect wirelessly or are inefficient in such connections.

Luma Home, Inc.

Luma Home, Inc.A conventional wireless router delivers limited coverage if you can’t hardwire additional Wi-Fi access points to it.

But providing consistent access across a space and never needing to tweak a network can be worth the higher cost for many users. Prices continue to drop year over year as capabilities increase, too.

How does mesh networking pull off this trick? What are the ideal circumstances to pay more for mesh over standalone base stations? And which should you consider? Let’s look into those questions in turn.

What is a wireless mesh network?

The concept of mesh networks first appeared in the 1980s in military experiments, and it became available in high-end production hardware in the 1990s. But due to cost, complexity, a scarcity of radio spectrum, and other limitations in early implementations, mesh didn’t gain a foothold until around 2015.

That’s when a number of startups and a few established hardware companies began offering expensive, but highly capable “mesh nodes,” which are network devices with wireless radios that contain software allowing them to configure themselves into an overlapping network without central coordination.

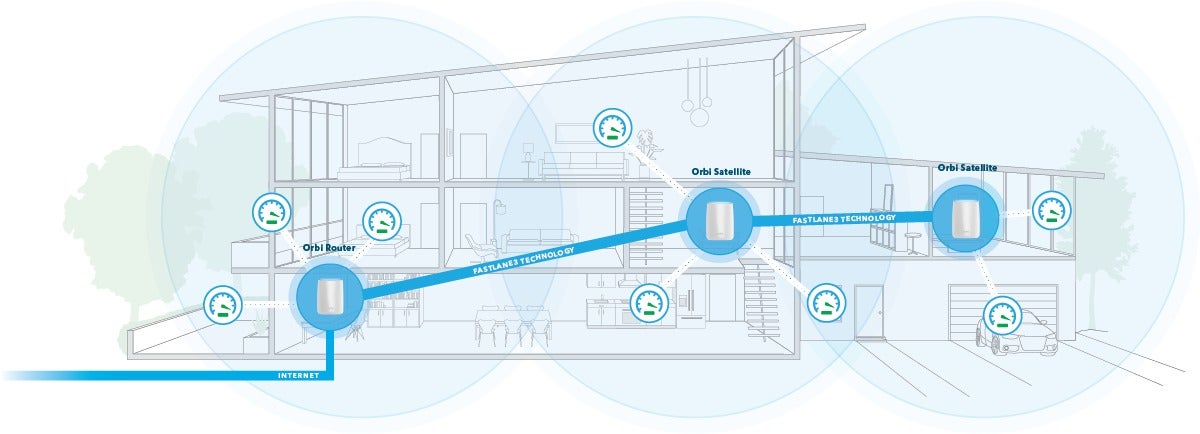

Netgear

NetgearMesh network routers, such as Netgear’s Orbi product line, connect multiple wireless nodes to blanket your home with Wi-Fi

In mesh networking, the fundamental unit isn’t an access point or gateway, but a “node.” A node typically contains two or three separate radio systems, and firmware that lets it talk with nearby nodes. Nodes communicate among each other to build up a picture of the entire network, even if some are out of range of the others. (An older Wi-Fi protocol, called Wireless Distribution System, was intended to connect base stations wirelessly, but it was very inefficient and never quite standardized.)

Client Wi-Fi adapters in phones, tablets, laptops, gaming systems, appliances, and other devices connect normally to these nodes, just as if they were standard network gateways or access points.

But behind the scenes, the mesh nodes determine the optimum route to transmit each packet of data from the first node that receives it to the node closest to its destination. A phone and a computer on the same network might connect to different nodes that relay the data directly between themselves. Or a Roku box at the far end of a house might receive streaming video across two intermediate nodes between the Roku and the broadband network.

The key value is that you don’t have to manage any of this. You also don’t need know anything about what’s happening under the hood. Because the nodes dynamically and constantly adjust radio and routing parameters, you always have the optimum performance and coverage.

The principle behind all wireless networking is “how do I transmit this number of bits in the smallest number of microseconds and get off and let someone else use it?” explains Matthew Gast, former chair of the IEEE 802.11 committee that sets specs used by Wi-Fi. Mesh networks manage this better than WDS.

In some cases, Gast notes, a mesh node might send a packet of data to just one other node; in others, a weak signal and other factors might route the packet through other nodes to reach the destination base station to which the destination wireless device is connected.

Netgear

NetgearNetgear will soon offer a version of its Orbi mesh router that connects to the internet via 4G LTE, instead of a cable or telephone line hardwired to the home.

When mesh networking first appeared, many nodes had just two radios, one for the 2.4GHz band and the other for 5GHz. The nodes had to mix handling Wi-Fi clients with data that needed to pass among them.

Fortunately, as products have matured, many nodes now sport three radios: simultaneous dual-band (2.4/5 GHz) networking for local connections to Wi-Fi clients and a 5GHz radio devoted to interconnections with other nodes. This can dramatically improve overall network throughput on busy networks by separating device-to-device and internet-based communication from node-to-node data exchange.

The goal is to make sure as much throughput remains reserved for actual productive traffic, such as streaming 4K video or making fast connections to internet multiplayer games, relative to that consumed by moving data around the network.

If a node is powered down or crashes—your cat gets a little too interested and knocks one off a shelf—the network doesn’t go down, too. As long as every node can continue to communicate with at least one other node, you still have a fully functioning network.

You typically rely on a smartphone to help set up the first node and network parameters and add additional nodes to an existing network. Mesh systems automatically reconfigure as you add nodes.

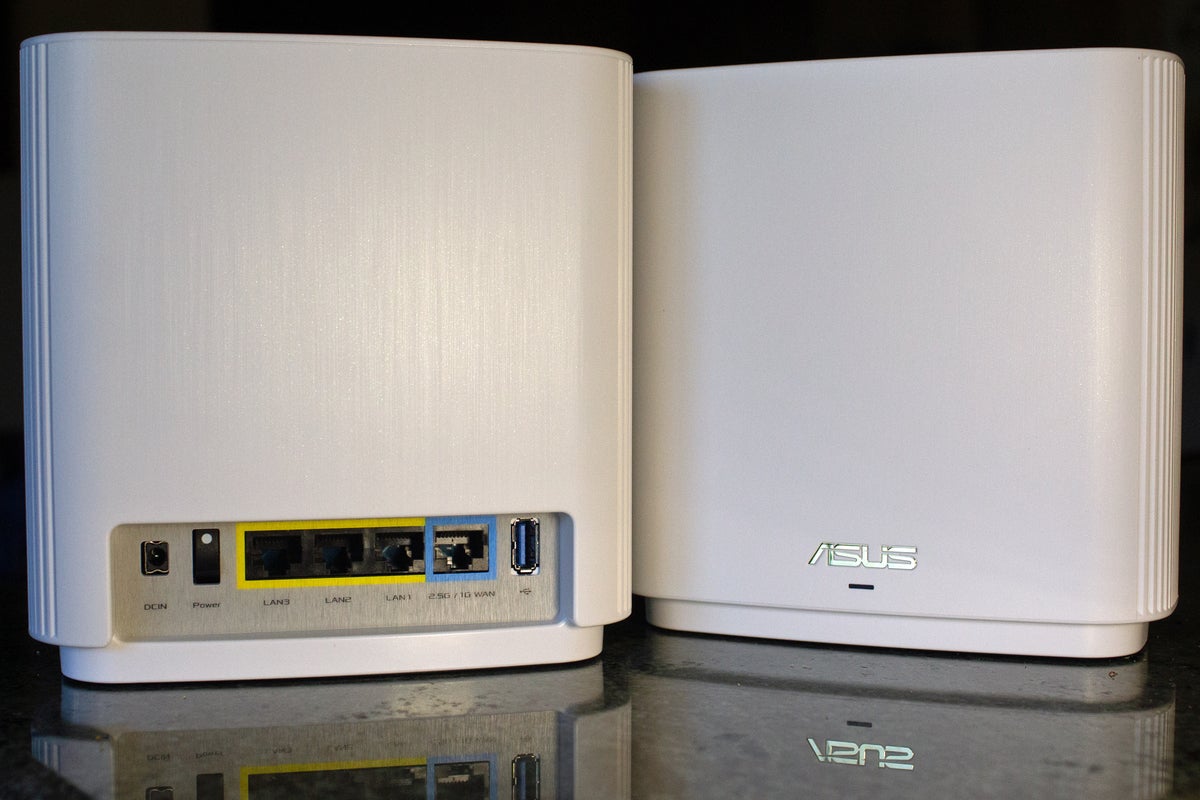

Michael Brown / IDG

Michael Brown / IDGTime was, you couldn’t find a mesh Wi-Fi router with a WAN port faster than 1Gbps. With routers like the Asus XT8, that’s no longer an issue. This mesh router features a 2.5Gbps WAN portg

Because you don’t have to plan around ethernet jacks or engage in elaborate testing when placing mesh nodes, deployment takes very little time and requires little fussing over time unless you move large pieces of furniture or add a lot more networked computers, gaming systems, or other devices.

Mesh systems also offer help in figuring out where to locate units, some of them using indicators on the nodes themselves while others require smartphone software. “There is an immense amount of engineering effort to make something very simple,” says Gast.

No two company’s products work together

The price you pay for network improvements? Proprietary protocols and higher sticker prices.

While Wi-Fi remains standardized, and extremely and reliably compatible among equipment from different makers, no two mesh systems on the market work with each other. An early mesh protocol, 802.11h, wound up being not just insufficient to the task, but entirely ignored by companies as they pursued better results and competitive advantages—and higher prices than for regular Wi-Fi gear.

The Wi-Fi Alliance, a trade group which controls the Wi-Fi trademark and develops lab testing for interoperability, created Wi-Fi EasyMesh in 2018 as a common point for manufacturers, most of whom are members. But as of 2020, the standard isn’t finalized, and only D-Link has committed (at CES 2020 in January) for newer products to support it fully.

With the pandemic underway, it’s unlikely we see substantial movement on EasyMesh in 2020. It’s the only potential standard that’s made any headway.

Netgear

NetgearNetgear has one of the few mesh network satellites engineered to operate outdoors; unfortunately, it can be used only with Netgear Orbi mesh routers.

As a result, when you buy into a system, you’re all in. If you want to expand your network and decide you don’t like the approach, coverage, or quality, you must get rid of all your gear and replace it with all new nodes. With standalone Wi-Fi equipment, you can effectively mix and match.

This mesh lock-in can also result in a problem if a startup maker of gear goes under or a well-established maker opts to stop producing new versions of its hardware or stop selling existing models. You might be stuck with the network you have, and some early mesh purchasers found that out the hard way, especially if a cloud component or specialized app was required for administration—and stopped being updated.

In 2020, however, it’s very likely that equipment purchased will have a multi-year lifespan because of the increasing investment and commitment by major manufacturers.

How to decide if mesh is right for you

Mesh hardware first came from startup companies, eager to grab a large chunk of home and small-office networking dollars by offering coverage and simplicity. As with most trends in electronics, however, a few startups fell by the wayside and most of the rest were purchased by large internet companies. Other established networking hardware makers joined the fray and have continued to improve their productsWith the current generation of gear, I suggest picking mesh over standalone Wi-Fi for these reasons:

- You have poor coverage, poor throughput, or jittery video streaming on your current network and want to improve any or all three of those factors.

- You don’t have ethernet wiring already in your home or office. (ethernet makes it easy to build a network with a single full-featured Wi-Fi gateway and cheaper, wired extenders. It’s also easy to upgrade to faster standard a little at a time.)

- You want the ability to improve network performance in the future by adding devices without managing placement and configuration.

- You want firmware updates handled automatically. (Some standalone routers offer this, too, but surprisingly few.)

- You never want to configure your network by connecting via a web administration interface and having to examine 100 options.

- You mostly want to never think about how your Wi-Fi network is running or how it works.

While any of the last few years of mesh networking systems can fulfill most of those promises, I strongly suggest only purchasing a new network system in which each node has three radios: two for Wi-Fi client access and one for node-to-node communication, as noted earlier. Otherwise, you’re not taking advantage of the best throughput possible with mesh.

Some nodes come with extras, such as a built-in gigabit ethernet switch, a USB port or hub for connecting printers and hard drives, and even an ethernet port to connect to other nodes that may be too far away to connect to wirelessly. If you don’t need these features, you can typically save money on the overall system cost.

Mesh networking is no longer a future waiting to arrive, but a fully realized present that can take the pain out of high-quality Wi-Fi networking.

This story, “Wireless mesh networks: Everything you need to know” was originally published by