[ad_1]

READER QUESTION: I am 59 years old, and in reasonably good health. Is it possible that I will live long enough to put my brain into a computer? — Richard Dixon.

We often imagine that human consciousness is as simple as input and output of electrical signals within a network of processing units – therefore comparable to a computer. Reality, however, is much more complicated. For starters, we don’t actually know how much information the human brain can hold.

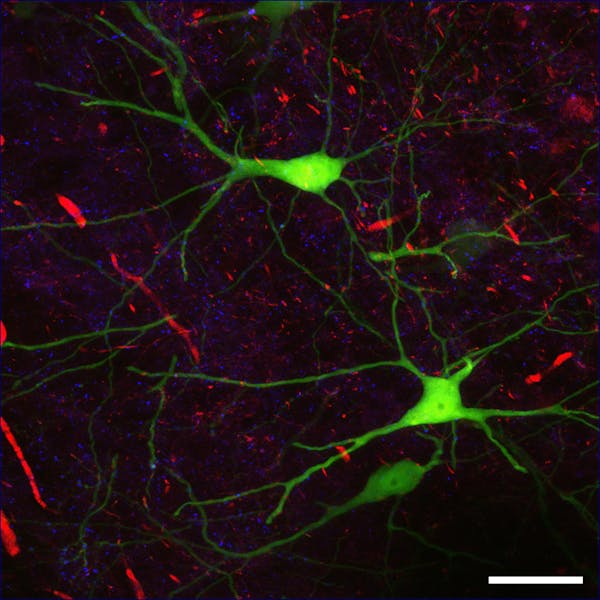

Two years ago, a team at the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle, mapped the 3D structure of all the neurons (brain cells) comprised in one cubic millimeter of the brain of a mouse – a milestone considered extraordinary.

This article is part of Life’s Big Questions

The Conversation’s series, co-published with BBC Future, seeks to answer our readers’ nagging questions about life, love, death and the universe. We work with professional researchers who have dedicated their lives to uncovering new perspectives on the questions that shape our lives.

Within this minuscule cube of brain tissue, the size of a grain of sand, the researchers counted more than 100,000 neurons and more than a billion connections between them. They managed to record the corresponding information on computers, including the shape and configuration of each neuron and connection, which required two petabytes, or two million gigabytes of storage. And to do this, their automated microscopes had to collect 100 million images of 25,000 slices of the minuscule sample continuously over several months.

Now if this is what it takes to store the full physical information of neurons and their connections in one cubic millimeter of mouse brain, you can perhaps imagine that the collection of this information from the human brain is not going to be a walk in the park.

Data extraction and storage, however, is not the only challenge. For a computer to resemble the brain’s mode of operation, it would need to access any and all the stored information in a very short amount of time: the information would need to be stored in its random access memory (RAM), rather than on traditional hard disks. But if we tried to store the amount of data the researchers gathered in a computer’s RAM, it would occupy 12.5 times the capacity of the largest single-memory computer (a computer that is built around memory, rather than processing) ever built.

The human brain contains about 100 billion neurons (as many stars as could be counted in the Milky way) – one million times those contained in our cubic millimetre of mouse brain. And the estimated number of connections is a staggering ten to the power of 15. That is ten followed by 15 zeroes – a number comparable to the individual grains contained in a two meter thick layer of sand on a 1km-long beach.

A question of space

If we don’t even know how much information storage a human brain can hold, you can imagine how hard it would be to transfer it into a computer. You’d have to first translate the information into a code that the computer can read and use once it is stored. Any error in doing so would probably prove fatal.

A simple rule of information storage is that you need to make sure you have enough space to store all the information you need to transfer before you start. If not, you would have to know exactly the order of importance of the information you are storing and how it is organised, which is far from being the case for brain data.

If you don’t know how much information you need to store when you start, you may run out of space before the transfer is complete, which could mean that the information string may be corrupt or impossible for a computer to use. Also, all data would have to be stored in at least two (if not three) copies, to prevent the disastrous consequences of potential data loss.

This is only one problem. If you were paying attention when I described the extraordinary achievement of researchers who managed to fully store the 3D structure of the network of neurons in a tiny bit of mouse brain, you will know that this was done from 25,000 (extremely thin) slices of tissue.

The same technique would have to be applied to your brain, because only very coarse information can be retrieved from brain scans. Information in the brain is stored in every detail of its physical structure of the connections between neurons: their size and shape, as well as the number and location of connections between them. But would you consent to your brain being sliced in that way?

Even if would agree that we slice your brain into extremely thin slices, it is highly unlikely that the full volume of your brain could ever be cut with enough precision and be correctly “reassembled”. The brain of a man has a volume of about 1.26 million cubic millimeters.

If I haven’t already dissuaded you from trying the procedure, consider what happens when taking time into account.

A question of time

After we die, our brains quickly undergo major changes that are both chemical and structural. When neurons die they soon lose their ability to communicate, and their structural and functional properties are quickly modified – meaning that they no longer display the properties that they exhibit when we are alive. But even more problematic is the fact that our brain ages.

From the age of 20, we lose 85,000 neurons a day. But don’t worry (too much), we mostly lose neurons that have not found their use, they have not been solicited to get involved in any information processing. This triggers a program to self-destruction (called apoptosis). In other words, several tens of thousands of our neurons kill themselves every day. Other neurons die because of exhaustion or infection.

This isn’t too much of an issue, though, because we have almost 100 billion neurons at the age of 20, and with such an attrition rate, we have merely lost 2-3% of our neurons by the age of 80. And provided we don’t contract a neurodegenerative disease, our brains can still represent our lifelong thinking style at that age. But what would be the right age to stop, scan and store?

Would you rather store an 80-year-old mind or a 20-year-old one? Attempting the storage of your mind too early would miss a lot of memories and experiences that would have defined you later. But then, attempting the transfer to a computer too late would run the risk of storing a mind with dementia, one that doesn’t quite “work” as well.

So, given that we don’t know how much storage is required, that we cannot hope to find enough time and resources to entirely map the 3D structure of a whole human brain, that we would need to cut you into zillions of minuscule cubes and slices, and that it is essentially impossible to decide when to undertake the transfer, I hope that you are now convinced that it is probably not going to be possible for a good while, if ever. And if it were, you probably would not want to venture in that direction. But in case you’re still tempted, I’ll continue.

A question of how

Perhaps the biggest problem we have is that even if we could realize the impossible and jump the many hurdles discussed, we still know very little about underlying mechanisms. Imagine that we have managed to reconstruct the complete structure of the hundred billion neurons in Richard Dixon’s brain along with every one of the connections between them, and have been able to store and transfer this astronomical quantity of data into a computer in three copies. Even if we could access this information on demand and instantaneously, we would still face a great unknown: how does it work?

After the “what” question (what information is there?), and the “when” question (when would be the right time to transfer?), the toughest is the “how” question. Let’s not be too radical. We do know some things. We know that neurons communicate with one another based on local electrical changes, which travel down their main extensions (dendrites and axons). These can transfer from one neuron to another directly or via exchange surfaces call synapses.

At the synapse, electrical signals are converted to chemical signals, which can activate or deactivate the next neuron in line, depending on the kind of molecule (called neuromediators) involved. We understand a great deal of the principles governing such transfers of information, but we can’t decipher it from looking at the structure of neurons and their connections.

To know which types of connection apply between two neurons, we need to apply molecular techniques and genetic tests. This means again fixating and cutting the tissue in thin slices. It also often involves dying techniques, and the cutting needs to be compatible with those. But this is not necessarily compatible with the cutting needed to reconstruct the 3D structure.

So now you are faced with a choice even more daunting than determining when is the best time in your life to forego existence, you have to chose between structure and function – the three-dimensional architecture of your brain versus how it operates at a cellular level. That’s because there is no known method for collecting both types of information at the same time. And by the way, not that I would like to inflate an already serious drama, but how neurons communicate is yet another layer of information, meaning that we need much more memory than the incalculable quantity previously envisaged.

So the possibility of uploading the information contained in brains to computers is utterly remote and might forever be out of reach. Perhaps, I should stop there, but I won’t. Because there is more to say. Allow me to ask you a question in return, Richard: why would you want to put your brain into a computer?

Are our minds more than the sum of their (biological) parts?

I may have a useful, albeit unexpected, answer to give you after all. I shall assume that you would want to transfer your mind to a computer in the hope of existing beyond your lifespan, that you’d like to continue existing inside a machine once your body can no longer implement your mind in your living brain.

If this hypothesis is correct, however, I must object. Imagining that all the impossible things listed above were one day resolved and your brain could literally be “copied” into a computer – allowing a complete simulation of the functioning of your brain – at the moment you decide to transfer, Richard Dixon would have ceased to exist. The mind image transferred to the computer would therefore not be any more alive than the computer hosting it.

That’s because living things such as humans and animals exist because they are alive. You may think that I just stated something utterly trivial, verging on stupidity, but if you think about it there is more to it than meets the eye. A living mind receives input from the world through the senses. It is attached to a body that feels based on physical sensations. This results in physical manifestations such as changes in heart rate, breathing and sweating, which in turn can be felt and contribute to the inner experience. How would this work for a computer without a body?

All such input and output isn’t likely to be easy to model, especially if the copied mind is isolated and there is no system to sense the environment and act in response to input. The brain seamlessly and constantly integrates signals from all the senses to produce internal representations, makes predictions about these representations, and ultimately creates conscious awareness (our feeling of being alive and being ourselves) in a way that is still a total mystery to us.

Without interaction with the world, however subtle and unconscious, how could the mind function even for a minute? And how could it evolve and change? If the mind, artificial or not, has no input or output, then it is devoid of life, just like a dead brain.

In other words, having made all the sacrifices discussed earlier, transferring your brain to a computer would have completely failed to keep your mind alive. You may reply that you would then request an upgrade and ask for your mind to be transferred into a sophisticated robot equipped with an array of sensors capable to seeing, hearing, touching, and even smelling and tasting the world (why not?) and that this robot would be able to act and move, and speak (why not?).

But even then, it is theoretically and practically impossible that the required sensors and motor systems would provide sensations and produce actions that are identical or even comparable to those provided and produced by your current biological body. Eyes are not simple cameras, ears aren’t just microphones and touch is not only about pressure estimation. For instance, eyes don’t only convey light contrasts and colors, the information from them is combined soon after it reaches the brain in order to encode depth (distance between objects) – and we don’t yet know how.

And so it follows that your transferred mind would not have the possibility to relate to the world as your current living mind does. And how would we even go about connecting artificial sensors to the digital copy of your (living) mind? What about the danger of hacking? Or hardware failure?

So no, no and no. I have tried to give you my (scientifically grounded) take on your question and even though it is a definite no from me, I hope to have helped alleviate your desire to ever have your brain put into a computer.

I wish you a long and healthy life, Richard, because that definitely is where your mind will exist and thrive for as long as it is implemented by your brain. May it bring you joy and dreams – something androids will never have.

This article by Guillaume Thierry, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, Bangor University, is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[ad_2]

Source link