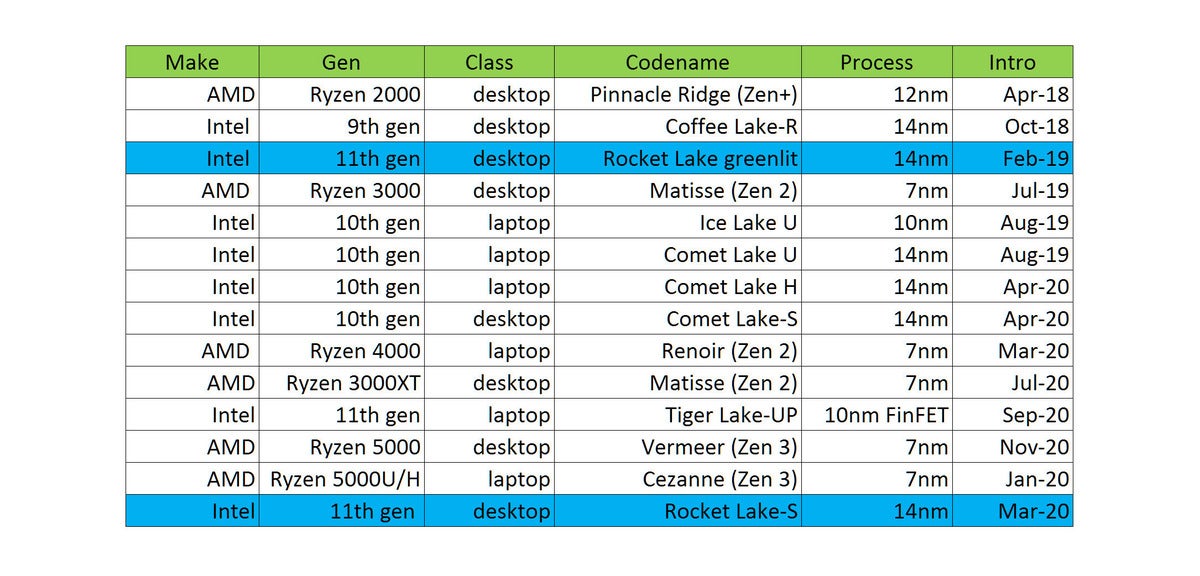

Intel’s 11th-gen Rocket Lake chip was green-lit well before AMD’s Zen 2 and Zen 3 architectures rocked our worlds, company officials acknowledged.

In an AMA posted Tuesday on the Intel subreddit, Scott Rouse, Intel’s platform engineer for Rocket Lake, attending with other Intel officials, revealed that Rocket Lake was given the go-ahead in early 2019. Its two-year journey to the launchpad on March 30th is actually break-neck speed for a new CPU (which might take years longer normally). Still, the world that Rocket Lake woke up to in 2021 probably wasn’t what Intel anticipated in 2019, when the company created the chip by marrying its yet-to-be-released 10th-gen, 10nm Ice Lake x86 cores with its already-aging 14nm manufacturing process.

The match wasn’t made in heaven. While our review of Intel’s flagship Core i9-11900K was kinder than most, others have strongly questioned whether the 8-core CPU should even have been made, given the step back in cores from the previous generation’s 10-core flagship. While we feel that’s an overly harsh opinion, it’s nevertheless interesting to learn that Rocket Lake’s approval came basically before AMD introduced its Zen 2- and Zen 3-based Ryzen CPUs.

ln the beginning of 2019, Intel had just successfully launched what was mostly a well-received 8-core Core i9-9900K chip. The Core i9-9900K didn’t win any power-consumption or value prizes against the top AMD CPU, but it claimed “best gaming CPU” and also held the multi-core performance medal.

IDG

IDGAMD Goes Ballistic

By July of 2019, however, AMD released its Ryzen 3000-series, built on a TSMC 7nm process. Then it dropped the mic with a true consumer-friendly 16-core CPU for $750. Up to then, Intel had been charging nearly $2,000 for its prosumer Core i9-9980XE CPU.

Intel’s response to the 16-core Ryzen 3000 chips would be a fairly anemic 10-core 10th-gen Core i9-10900K, launched in April, 2020, built on the same cores as the previous generation. It held strong in gaming but put nary a scratch in AMD’s multi-core performance and value lead.

Perhaps at this point, it might have looked like a good time to cut bait or change course. But with gaming performance still clenched in its teeth, and arguably better application performance, Intel likely held out hope that Rocket Lake could justify its 8-core existence in a 16-core chip world.

Then came Zen 3…

By November of 2020, the situation worsened for Intel’s CPUs with the debut of AMD’s Ryzen 5000. Based on a redesigned Zen 3 core, it snatched away Intel’s last shreds of single-threaded and gaming performance advantages. AMD ruled multi-core and single-core performance alike, and it had a solid lead in gaming, too.

Rouse doesn’t get into the whys or wherefores going into the Rocket Lake launch, but you can guess that after 21 or so months of making the 11th-gen desktop chip a reality, there was no turning back. Rocket Lake launched into a considerable headwind.

Whether Rocket Lake is judged a success—professional critics and Internet peanut gallery aside—won’t be known for years.

Could Rocket Lake have had more cores?

So much of the criticism of Rocket Lake seems centered on the regression in core count. Some have wondered why Intel bothered to “waste” valuable die space on the graphics core. If it had simply dedicated that to two more cores, wouldn’t that have been more prudent considering it’s actually priced against AMD’s 12-core Ryzen 9 5900X?

“A 10-core die without integrated graphics would have been a second die (design effort) as integrated graphics is a hard requirement for commercial customers,” Rouse responded. “Not developing the design for a second die was a business decision.”

By business decision, Rouse speaks to the business of trying to make one thing or very slight variations of it to sell to many people. While the vast majority of gamers and enthusiasts all run discrete graphics, Intel uses the same die for both gamers who rarely need that IGP, to boring business customers who almost always use integrated graphics.

Lest you think integrated graphics is pointless, Intel’s Aaron McGavock said Intel’s research shows more than 70 percent of its customers rely on integrated graphics.

Intel isn’t the only company or business that sells different products based off one design or parts bin. Everything from cars to shoes is made with some reuse of the same building blocks. McGavock acknowledged that Intel is partially handcuffed by its current monolithic design, which can force a high-performance gamer to take the same product features that may appeal more for consumer PCs.

That, however, will change, McGavock said.

“We are working on solutions, which include more modular designs, but for now we have the monolithic, large die that has to fit a variety of usages,” he said.